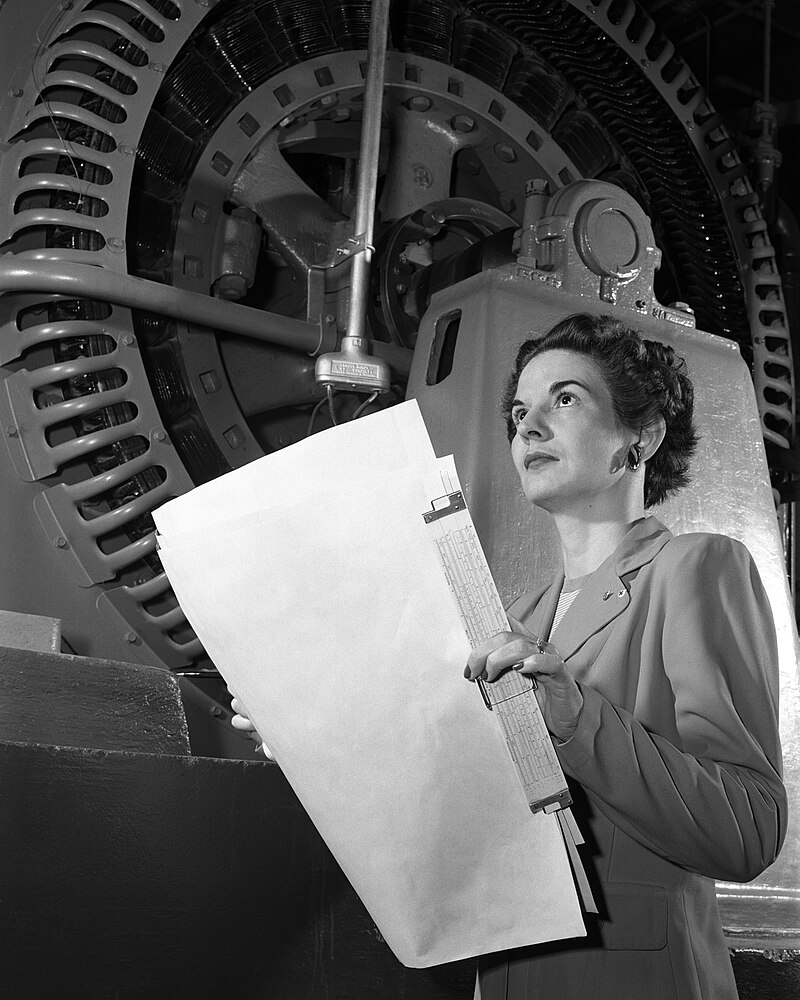

In black-and-white photos, she’s the polished, professional woman standing at the back of a giant wind turbine. Her gaze is fixed and determined.

Kitty O’Brien Joyner was the first female engineer to be hired by the agency that would become NASA. She was an electrical engineer who powered the wind tunnels at Langley Research Center, where World War and Cold War aircraft were tested.

She was also the first woman to graduate from the University of Virginia with an engineering degree, in 1939.

But who was this trailblazer as a person?

Kitty O'Brien Joyner was a pathbreaking engineer at UVA and beyond.

With UVA celebrating the 50th anniversary of its first fully co-educational graduating class this year, leaders of the School of Engineering and Applied Science were curious to learn more about the driven young engineer who was decades ahead of her time at the University, and in the broader culture.

Informed by the observations of Joyner’s daughter — her only surviving child — and a deep dive into archival documents, this is the story of a historic figure who would not be deterred.

“Kitty O'Brien Joyner was a pathbreaking engineer at UVA and beyond,” said Jennifer L. West, who became UVA Engineering’s first female dean in 2021. “Her work at Langley had significant impact on advanced avionics and hypersonics.”

She Found Her Way After a Loss

Kitty Wingfield O’Brien was born July 11, 1916, in Charlottesville, near the University of Virginia. Her middle name echoed the maiden name of her mother, Ruby. Her father, Edwin Kell O’Brien, was a successful UVA alumnus.

Kitty enjoyed an exuberant childhood. The family's Rugby Avenue farm came complete with chickens, pigs and a milk cow. Kitty and her older sister, Martha Anne, loved to ride their horses on a trail that led from their property to what is today the shopping-oriented Barracks Road.

“The roads then were nothing but dirt,” said Kitty’s daughter, Kate Bailey, now in her 70s. “When they were driving home, my grandfather would turn into the driveway, aim his car at the ruts in the Albemarle County clay and take his hands off the wheel. The ruts and the downhill pull of gravity would drive them to the house.”

The family lived in a home that Edwin designed himself. He was an 1897 engineering graduate who worked as a traveling civil engineer for DuPont. He had patented devices, including one to place explosive charges in the ground and another for an agricultural spray apparatus.

Edwin loomed large in Kitty’s mind. She dreamed of becoming an engineer like him.

Yet that often led her to wish she were a boy, so that the dream would be possible.

While there had been a relative handful of women who had become engineers in the United States since the 1800s, either by degree or through practice, the examples Kitty saw were all men. She had an uncle and a cousin who were engineers as well.

But it was her father, who also tended the farm, who taught her the power of hard work and how far it could take a person.

Sadly, Kitty’s idyllic childhood ended in December 1931. Edwin, who had since retired, died at University Hospital three weeks following a stroke. He was 60.

Kitty was only 15.

“It just broke her heart,” Bailey said. “She adored her father.”

The loss, however, affirmed her career choice. “That was her motivation for wanting to become an engineer, and she wanted to become a civil engineer.”

She Was Smart and Focused

In 1936, Kitty applied to UVA to follow in her father’s footsteps. It was 100 years after the School of Engineering had been established.

Though the population of enrolled women across Grounds had reached triple digits due to a 1920 policy change — “women of maturity and adequate preparation” would be considered for UVA’s graduate and professional schools — no woman had yet graduated as an engineer from UVA.

As Kitty focused on her goal, she first had to navigate the formal policy's special conditions, which included two years of education elsewhere.

She attended Virginia’s all-female Sweet Briar College. There, she showed she could handle the math and physics expected.

She also proved herself to be well-rounded. She served on the student newspaper as an assistant editor and a news reporter.

With proof of her abilities established, Kitty and her mother petitioned Walter S. Rodman, dean of the School of Engineering, for Kitty to be accepted into the undergraduate program.

Upon her transfer, Kitty herself became front page news. The Sweet Briar News article, “Former Student Begins Career,” mentioned that she joined a fall head count of 160 men.

She Thrived in Engineering School

The 1930s was a decade of unprecedented growth at UVA. The new home to the School of Engineering, Thornton Hall, was a Public Works Administration project completed in 1934. The academic building was the first on Grounds west of Emmet Street.

If Kitty worried about her reception as she entered the new building in the fall of 1937, her fears were put to rest.

“She said that the guys were incredibly supportive and friendly with her,” Bailey said. “She was also the type of person, though, that if a few people were jerks, she wouldn’t have mentioned it.”

Tensions between male and female students apparently had become less dramatic since the first women arrived at UVA in the 1920s — a time when some men stomped as a woman entered a room or spoke. Though there was more progress to be made, Kitty’s can-do attitude in a hands-on field surely helped.

Even so, the duality was noted.

“At that time there were two bathrooms in the engineering building, one of them labeled ‘MEN’ and the other labeled ‘MISS O’BRIEN,’” Bailey said with a laugh.

Many of the male friendships her mother made at the University were lasting, Bailey added.

She Was ‘Vivacious’ and Pragmatic

It was clear from Kitty’s decision-making in college that she viewed being a professional as requiring both ability and flexibility. She had declared her interest in becoming a civil engineer, for example. Yet she had been persuaded by Dean Rodman that a woman stood a better chance of success by focusing on electrical engineering. It had nothing to do with aptitude. He felt the realities of construction sites, including a lack of restrooms for women, would put her at a disadvantage.

The decision would be fortuitous for her role in the war effort. Only she didn’t know it yet.

She was newly focused on lighting.

General Electric made the first fluorescent lamps for sale, improving quality and longevity over incandescent lights. By 1938, fluorescent models and wattage began to vary based on application. Kitty saw in the development an opportunity to both do some substantive research and position herself for a future job.

Electrical engineering is scarcely considered a feminine profession...

She may, too, have sought a recommendation from professor Lawrence R. Quarles, a former employee of Westinghouse, GE’s main competitor. Westinghouse had hired the first female engineer in the country, Bertha Lamme, in 1893. Lamme was a mechanical engineer who specialized in electricity. Thereafter, the company continued to stand out for its hiring of women in electrical manufacturing.

Kitty was interviewed in her final year at UVA about her career prospects. The American Institute of Electrical Engineering had selected her paper, “Fluorescence, the Light of the Future,” as a district finalist for its annual collegiate competition. She presented the paper at their conference in Miami that November. A reporter for The Miami News chronicled her second-place finish under the headline "GIRL ENGINEER TALKS: Kitty O'Brien Finds Field 'Opportunity for Women.'"

Kitty was a novelty, and the article presents her as such. “Electrical engineering is scarcely considered a feminine profession…” the piece begins.

It goes on to note her pragmatism. “Her interest is principally in the field of lighting, and she feels that a woman, combining technical skill and natural intuition, is in a better position to design lights and household appliances than men.”

In addition to her participation with the electrical engineers’ group, where she served as secretary for the Virginia student membership, the article details that the “vivacious girl” was president of the Chi Omega chapter at UVA, president of the Women Students’ Association and an honorary student member of the Trigon engineering society.

And while fairly presenting her credentials, the reporter, as per the times, also makes note of her physicality in a way that would be blanching for a professional woman today.

“Miss O’Brien attired in a sports dress of rose beige, her dark hair done up in the latest style coiffeur, reflected enthusiasm and her brown eyes sparkled…”

By her last semester, Kitty had taken serious coursework in such areas as hydraulics, applied mechanics, electronics, and AC and DC machinery. She was among the 38 engineering students who passed their final exams that spring.

Kitty graduated on June 12, 1939, with a Bachelor of Science in engineering — the first woman at UVA to do so.

She Took a Chance on Langley

Though Kitty’s future was bright, it wouldn’t involve household lighting.

Instead, she would specialize in the electrical operation of wind tunnels run by a government group whose name few people would recognize today: the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

The NACA Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory, located in Hampton, Virginia, was the oldest such facility in the nation. Congress created it in 1915 in response to aviation improvements observed in the European theater during World War I. Adding new wind tunnels was critical to the U.S. taking the lead in airplane development.

Not until more than four decades later would the organization become NASA.

It was the summer after her graduation, while on vacation on the Virginia Peninsula, that Kitty took a chance and applied to the young agency, which was building a reputation worldwide for pioneering flight design improvements.

By 1939, U.S. involvement in World War II became more likely following Germany’s occupation of Poland and the Sept. 3 announcement of war by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

That same month, Kitty was hired as a junior civil engineering aide. She was the first woman engineer in NACA’s almost 25-year history.

On a webpage, NASA explains the sweep of NACA’s influence, which would essentially be the scope of Kitty’s career: “NACA research led to advances in aeronautics that helped the Allies win World War II, spawned a world-leading civil aviation manufacturing industry, propelled supersonic flight, supported national security during the Cold War and laid the foundation for modern air travel and the space age.”

She Helped Win the War

Wind tunnels are apparatus that replicate the effects of airflow on an object. By the time Kitty arrived at NACA, the world’s largest wind tunnel — 30-foot by 60-foot — had been constructed there. No longer would the lab have to test at model scale. The tunnel was big enough to generate realistic winds on actual aircraft.

According to Steven T. Corneliussen, writing for the NASA History Series, one main goal was to avoid “compressibility” of air around airfoils — the shaped surfaces on a plane that can create lift or drag. “Gust testing” challenged aircraft stability. Designs that worked in theory didn’t always hold up when all the nuts and bolts were in place. “Drag cleanup” allowed for designs with reduced resistance, improving aircraft speed and range.

NASA explains in another article on the history of the full-scale tunnel that it operated “around the clock” every day of the week.

“Early versions of virtually every high-performance fighter aircraft were evaluated in the [Full-Scale Tunnel], allowing for countless design improvements that gave American pilots a critical edge in combat.”

With the generation of all that wind current came the increased need for electrical current and power reliability. It was in that intense setting that Kitty rose, laboring in the tunnels and taking greater responsibility for the electrical schemes as new tunnels were built.

Kitty was a trailblazer in a field that was blazing new paths at the same time.

Though lead engineers among the expert staff could be “tough” and “assertive,” the culture was also collaborative, Corneliussen says. Lunchtime conversations, for example, often left it unclear who came up with the latest great idea.

“Kitty was a trailblazer in a field that was blazing new paths at the same time,” said Christopher Goyne, a UVA Engineering professor and director of UVA’s Aerospace Research Laboratory. “Wind tunnels such as the ones that Kitty worked on at NACA require electricity. The electricity powers fans and compressors to generate the air flow. Electrical engineering expertise is also needed to develop the instrumentation to measure the air flows. So Kitty’s contributions would have been critical to the development of the NACA wind tunnel capabilities at Langley, which became world-renowned.”

The U.S. would go on to assert air superiority in the European and Pacific theaters in 1944, a full year before the war would culminate — thanks in large part to NACA.

She Valued Work, Home, Community

Kitty continued to move up in the ranks, analyzing the electrical operation of multiple wind tunnels — as she was depicted in 1952 NACA publicity photos. She managed subsonic and supersonic facilities.

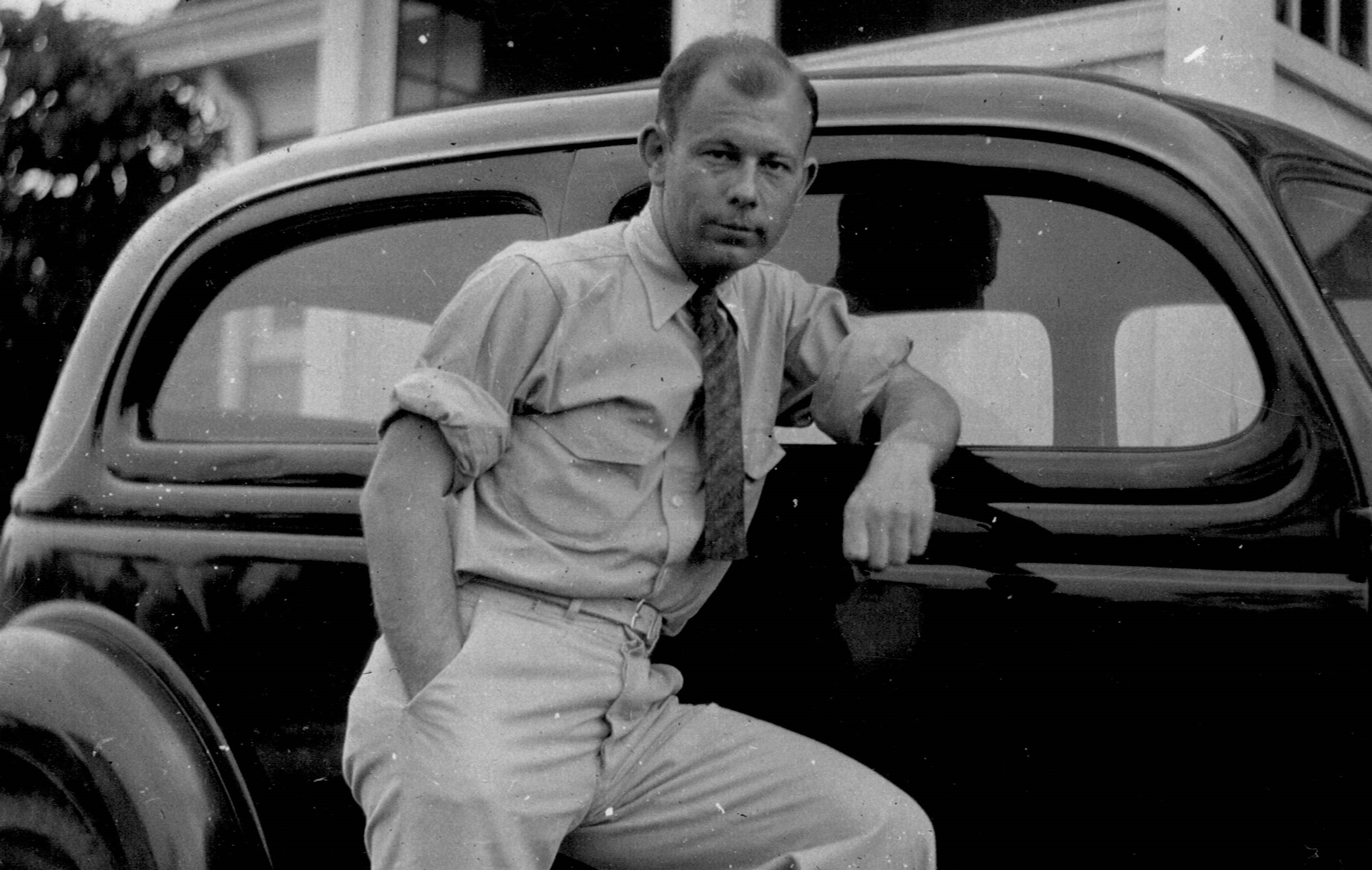

It was shortly after starting at the organization that Kitty married her colleague, Upshur Joyner, a physicist who had been at NACA when she arrived. Upshur knew the Langley wind tunnels well. The William & Mary graduate got his start there as an assistant scientific aide. When he met Kitty, he had risen to conducting thermodynamic tests and performing other advanced studies on planes.

The couple married on Sept. 13, 1941. In her wedding announcement, Kitty proudly noted her work in Langley’s electrical maintenance department.

The Joyners would go on to have two children — son Sam (born Upshur O’Brien Joyner, a future design engineer) and daughter Kate (born Kitty Wingfield Joyner, a future nurse).

Kitty was interviewed in December 1957 about her work, home and social life for the recurring “Peninsula Portraits” in the (Newport News) Daily Press. A photo caption bestowed the title “homemaker-engineer.”

“Of course, there have been others since,” Kitty said, briefly acknowledging her professional claim to fame, “and now engineering is considered a good field for women to enter.”

Soon after NACA became NASA in 1958, space capsules were being tested in the wind tunnels. And women, including the first Black woman to become an engineer at NASA, Mary W. Jackson, were among the now-famous “human computers” who did the math to get the U.S. to the moon.

“Several of those ‘computers’ were her good friends,” Bailey said. “They played in a bridge group together, and the big thing in bridge is counting points and keeping track of all of that in your head, so the game play was rapid-fire.”

“I remember my parents talking about the astronauts with whom they had lunch at work that day.

Bailey recalled first realizing that her mother — who not only had a career when most women did not, but a career at NASA — was exceptional.

“I remember my parents talking about the astronauts with whom they had lunch at work that day,” she said.

When her parents had a conversation, it was an exchange between two equals. However, in front of others, the discussions were often simplified or left key details unsaid. It was only in retrospect, Bailey realized, that her mom and dad were at times talking about top-secret projects.

Despite NASA’s exacting work environment, family life was normal, Bailey reported.

An avid gardener, her mom often used planting or weeding as a stress-reliever before heading to work in the mornings — always immaculately dressed.

She Never Stopped Being a Role Model

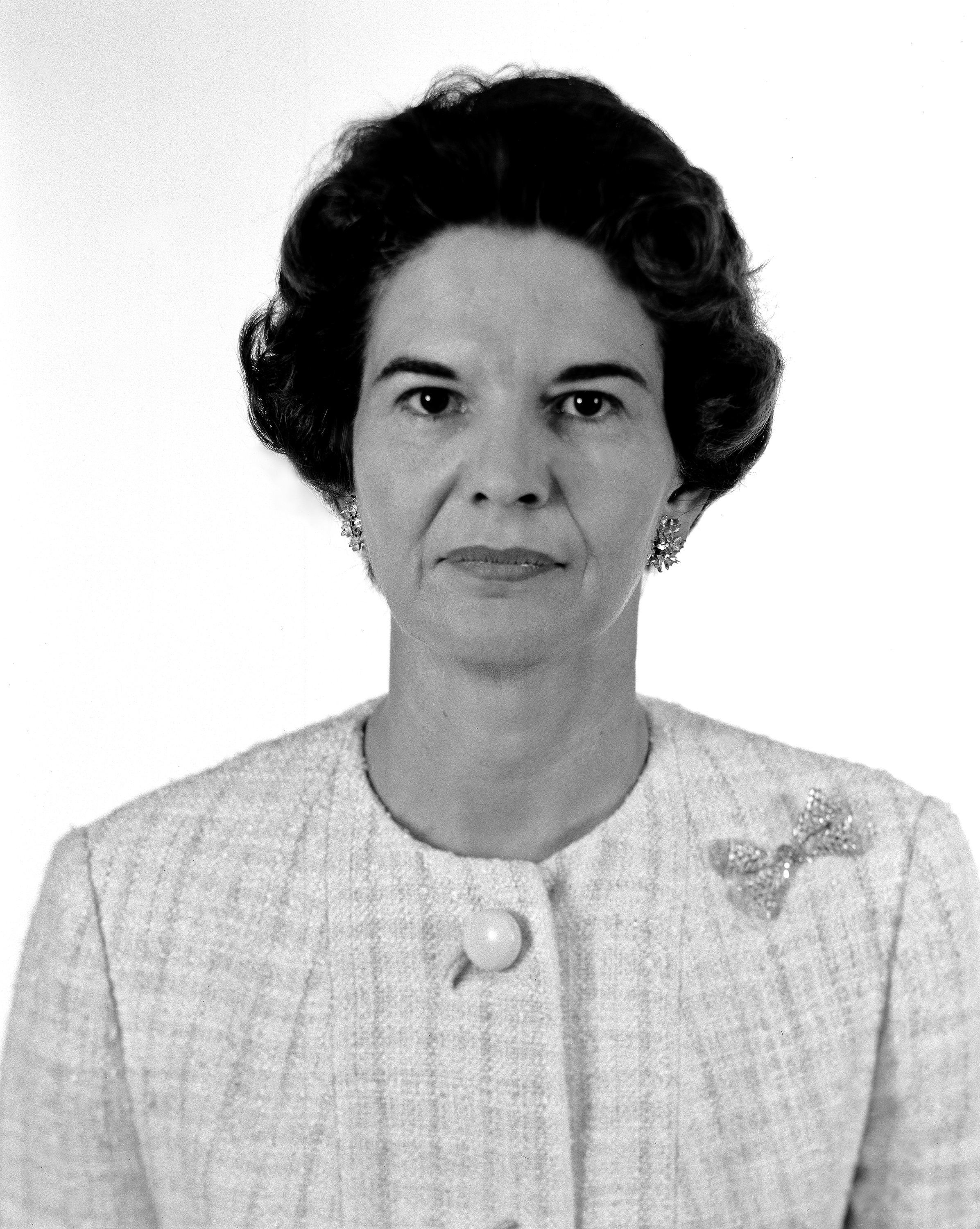

Kitty spent her entire career at the federal agency, providing more than 30 years of public service. After about a decade in a senior leadership position as branch head of the Facilities Cost Estimating Branch, Office of Engineering and Technical Service, she retired in 1971.

She had enjoyed maintaining her contacts and was good at the analysis involved in projecting construction costs, but “she would have much rather have been out doing more hands-on stuff in the wind tunnels,” Bailey said.

However, at no phase of her mother’s life did she stop being the person she was raised to be. She never sought recognition as the first female engineer at NASA or at UVA, nor for anything else she accomplished in her field. Quiet service was enough.

“Character always meant so much more to her than any sort of technical achievement,” her daughter said.

Illustrating the point, the accolade that remained closest to her mom’s heart, Bailey said, was the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award, which Kitty won at graduation. The national honor, bestowed at select universities, is given to two members of a graduating class and one member of that university’s community. It recognizes “excellence of character and humanitarian service.” Other notable recipients of the award include Eleanor Roosevelt, Mister (Fred) Rogers and Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell Jr.

Kitty stayed engaged in the engineering community as a member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and as an honorary life member of the Engineers Club of the Virginia Peninsula. She also was a member of service organizations, including P.E.O., which helps women pursue their education.

She was active in her many groups until her health no longer allowed. Following complications from a fall that affected her spinal pressure, spurring the onset of dementia, Kitty died on Aug. 16, 1993, at age 77.

Upshur died three months later at age 85.

What Bailey remembers most about her mom was her emphasis on responsibility, the sciences and being a good human being. The daughter is the last keeper of her mother's legacy. But others are starting to learn more about Kitty.

In 2022, NASA posted an article quoting female interns about the women who inspire them.

“I admire [Kitty O’Brien] because she was the first woman engineer in a male-dominated industry, which did not prevent her from paving her way to success and establishing a standard for girls and women everywhere,” said NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center intern Rasha Shreim. “Her perseverance inspires me, especially when she had to fight for her education to get accepted into a school that was structured for males only.”

West, the Engineering School’s dean, was so inspired that she shared Kitty’s story as her address to this year’s engineering graduates. The school has achieved 34% female enrollment — more than 10 points higher than the national average. The dean aspires to keep climbing.

“We honor the legacy Kitty left by paving the way for future generations of engineers,” she said.