In disaster films like “Armageddon,” “Greenland” and “Deep Impact,” the stories revolve around some variation of a big rock from outer space on a crash course with Earth, threatening extinction.

Maybe only one scientist or scientific branch knows about the near-Earth object at first. Should they notify the White House? How will they stop it?

A better question yet: Could something like this really happen?

Joshua Handal, who earned a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science in 2012, is a good person to ask. He serves as a program analyst with the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office. The unit is responsible for integrating efforts that protect us from near-Earth objects.

Handal said during a return visit to the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering on Friday that the dramatic scenarios found in those blockbuster movies are both realistic and unrealistic. He was joined by his boss, Kelly Fast, acting planetary defense officer in the Planetary Defense Coordination Office at NASA Headquarters. She also manages the Near-Earth Object Observations Program. They spoke to a small group before the afternoon seminar “Finding Asteroids Before They Find Us: Planetary Defense at NASA,” which featured Fast as special invited guest along with Lindley Johnson, PDCO officer emeritus.

“Our job is quite literally safeguarding the planet from a potentially catastrophic day,” he said.

Previously, Handal served as a NASA public affairs officer and led strategic communications for various NASA missions, including for the agency’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission, also known as DART.

Here is some of the bad and good news that Handal and Fast shared that morning.

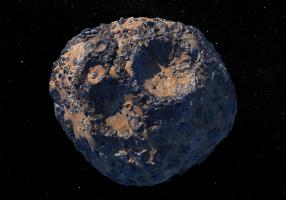

Asteroids 140 meters in diameter and larger — so-called “city killers” — are circulating near Earth. But scientists know of no collision threats for generations ahead.

The Planetary Defense Coordination Office coordinates with other nations’ space agencies through the United Nations-endorsed International Asteroid Warning Network and the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group.

NASA and other scientists around the world look to the skies and run computerized predictions based on the orbits and trajectories of objects that will come near Earth, gaming out the likelihood of a collision.

“It’s not a pinpoint,” Handal said. “There’s still some uncertainty.”

However, the sheer number of the asteroids (primarily made of rock), comets (primarily made of dust, ice and frozen gases), and meteoroids and meteors (primarily made of rock and metal) are cause for concern.

NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Objects Studies estimates that there are about 25,000 near-Earth objects, or NEOs, that are 140 meters in diameter or larger that both orbit our sun and pass close to our planet’s orbit.

At just under 500 feet, that’s equivalent to the height of the world’s tallest statue, India’s Statue of Unity, or the smaller end of what’s considered a skyscraper.

But most known NEOS of 140 meters or larger don’t come close enough to Earth to pose a threat, and are unlikely to in the next 1,000 years. Prediction models have an even greater degree of certainty 100 years out.

NASA hasn’t identified all of the asteroids and other near-Earth objects they think are out there. But a new telescope is in the works to help close the gap.

Of the NEOs whose trajectory NASA is able predict, only an estimated 43% of those believed to exist among a wider field have been found. But Handal said trajectories often change as asteroids get closer to Earth. And if one were on a crash course, the world would have time to do something.

What’s more, it’s not just NASA watching. In addition to other space agencies, there are additional professional and amateur astronomers who keep track.

“The problem with the movies is one person knows, and they have to decide if they’re going to go wake up the President,” Handal said. “First of all, astronomers around the world would say on their channels that there’s this object. Second, all of our data is made public by design.”

However, there is an issue with how much data is available due to the limits of the world’s current telescopic network.

“We have what’s called a ‘field of regard’ problem,” Handal said. “You can’t point a telescope at the sun, so we have to rely on the night time sky. In 2013, we actually had a small impact in our atmosphere, and it came from daytime sky, causing some air bursts. That actually woke a lot of people up on an international level."

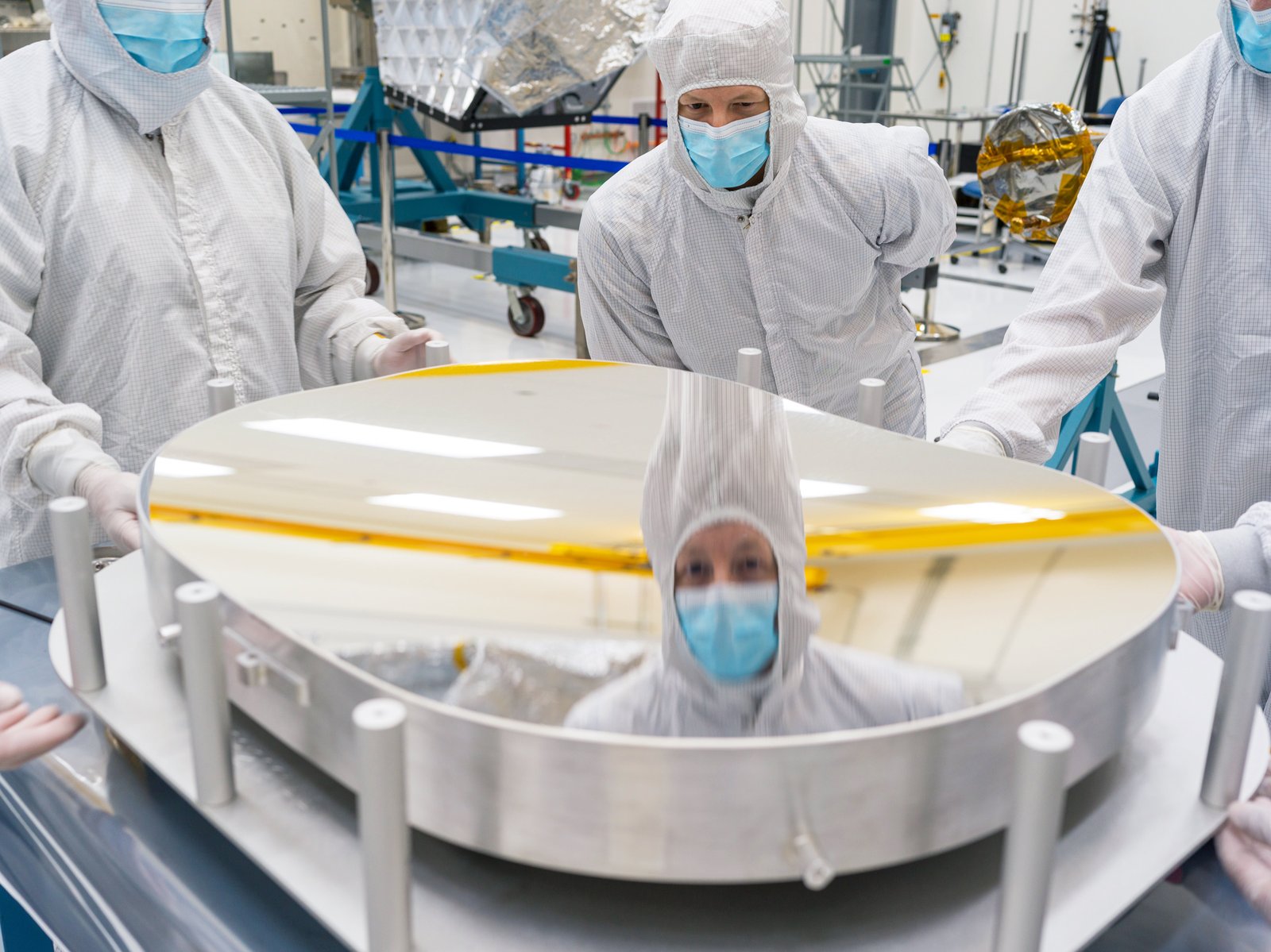

To solve the problem, NASA plans to launch the NEO Surveyor satellite telescope in 2027, which will stay in orbit on sunward side of the Earth and use infrared as part of its sensor package. While the telescope is expected to increase the range of near-Earth object identifications to 90%, “no one telescope can see everything at one time,” he said.

He added, “Asteroids don’t reflect a lot of light, but infrared will help with determining their size.”

FEMA doesn’t have a depth of protocols, as it does with other types of natural disasters. But NASA proved that an asteroid can be “pushed,” and FEMA is preparing if that's not possible.

What happens if a massive NEO is on a course to bump into our planet?

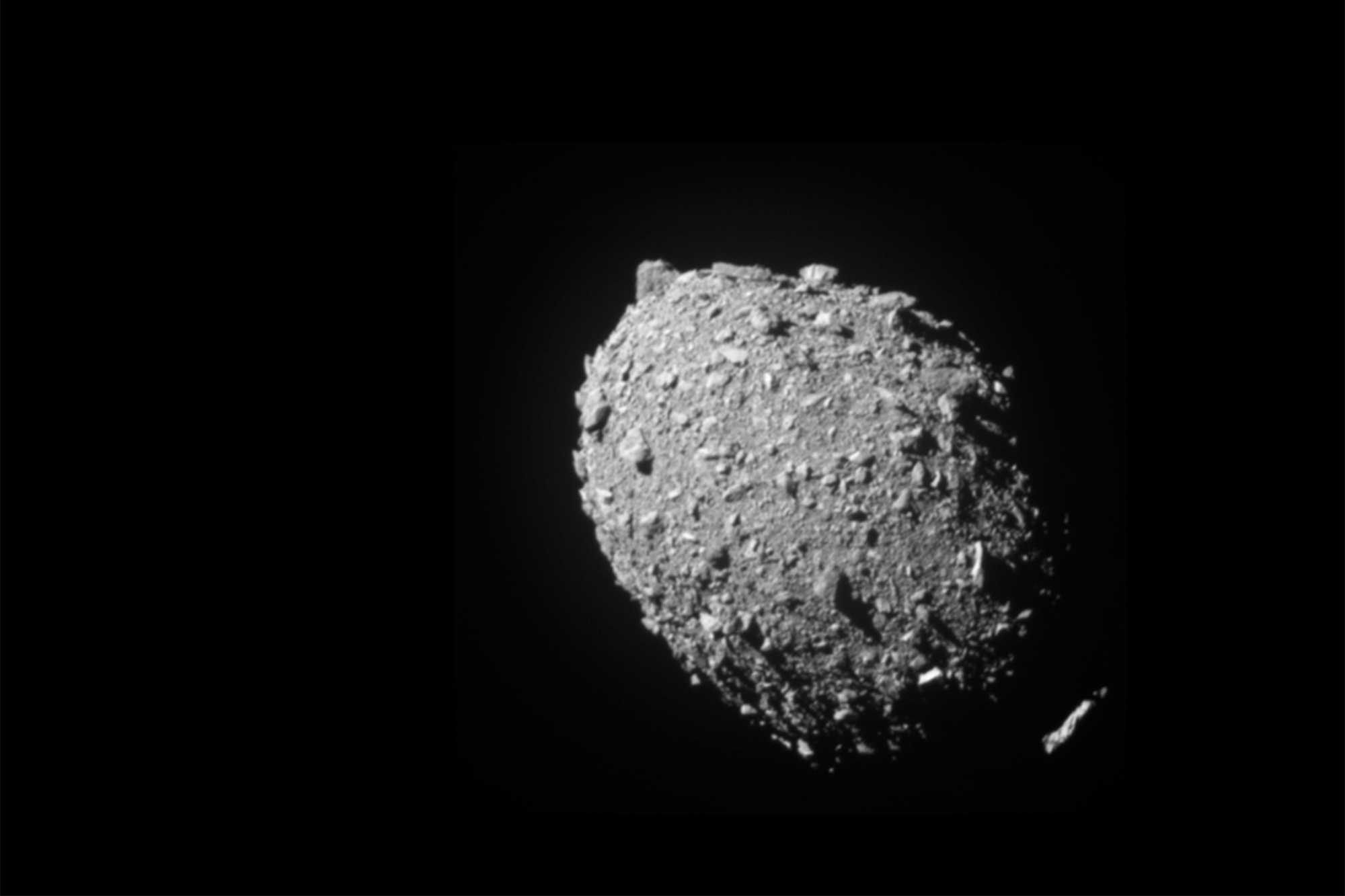

In 2022, NASA successfully demonstrated its Double Asteroid Redirection Test. The rocket performed the feat of striking a moving asteroid “moonlet” from 6.8 million miles away, nudging it off its trajectory.

A moonlet rotates around a larger asteroid, much like the moon rotates around our planet as a natural satellite.

Handal compared the smaller asteroid, named Dimorphos — 525 feet in diameter — to the size of one of the Great Pyramids. He compared the DART to the size of an industrial refrigerator traveling at 4 miles per second, “extremely quickly.”

Though the Earth was never in danger, because the rocks were never near our path to begin with, the proof of concept encouraged NASA.

And, “If we can’t do that, we’ll work with FEMA to see if we need to evacuate people on the ground,” Handal said. “Our role in that instance would just be to provide the most accurate data we can.”

FEMA now has a planetary defense officer, and the agencies have begun to work closely together, Handal stated.

DART might not work for a bigger object or one that’s differently structured. But there likely would be enough lag time for a mission.

“Dimorphos was something we call a ‘rubble pile,’” Handal said. “If you look at DART’s final images, you’ll see what the surface looks like. It’s more like a sandy beach situation. If Dimorphos were more solid, would it have been deflected as much as it was? We don’t know what each asteroid is like. What we’ve found [so far] is they can be a pretty diverse population and that may feed into how we deflect something.”

But, as the expression goes, forewarned is forearmed. He gave as an example a 14-year lead time based on computer modeling. That could result in a manned or unmanned reconnaissance mission to get a closer look at the object’s composition. That data then could be used for more precise planning.

“Do we want to immediately fly a recharacterization mission? Would it be a rendezvous or just a flyby? We might later find that the NEO is not a threat, but we want to explore all the possibilities for dealing with uncertainties.”

Even so, Handal’s colleague Fast said, “You only have so many opportunities to launch something at an asteroid. Missions for science can take five, six, seven years. Then there are the launch opportunities. To send a spacecraft to Mars, for example, you have to wait every two years to do that.”

Even relatively small near-Earth objects can be disruptive. But there are a lot of people around the world paying attention and seeking to work together.

Sometimes you’ll look into the night sky and see shooting stars. They happen numerous times of year with meteor showers, which tend to be harmless.

More rarely, a meteor can appear to be a very bright fireball called a “bolide.” The 2013 daytime event Handal mentioned, the Chelyabinsk meteor, shattered windows in Russia with its explosive shock wave.

The PDCO formed in 2016 with a congressional mandate to pay close attention to these types of occurrences, and to prepare for any large NEOs.

Since then, the U.S. has begun engaging in tabletop exercises with other countries to work through how responses from potential scenarios might play out. That includes something very large and unexpected — the kind of object that would be no match for DART.

“We have international space treaty,” Handal said. “We can’t just nuke it. What precedent would we set if we did violate that? We have to start having these conversations in a very candid way. We want to make sure another nation doesn’t think we’re just moving the asteroid and deflecting it over to their nation.”

In that regard, the need to work with nations such as China is obvious, the two NASA spokespeople said.

“We can’t bilaterally engage with China, but we can multilaterally,” Fast noted.

The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space recommendation was to have an International Asteroid Warning Network, which NASA now leads. The space agency ties together scientists from within its divisions together with large institutes, small observatories and even amateur setups worldwide.

“It’s possible in the future we’ll even have in-space collaborations,” Handal said. A major threat “may not happen in our lifetimes, but the nice thing is everyone is talking about it now.”

Handal's visit was made possible thanks to the support of the Clark Scholars Program.