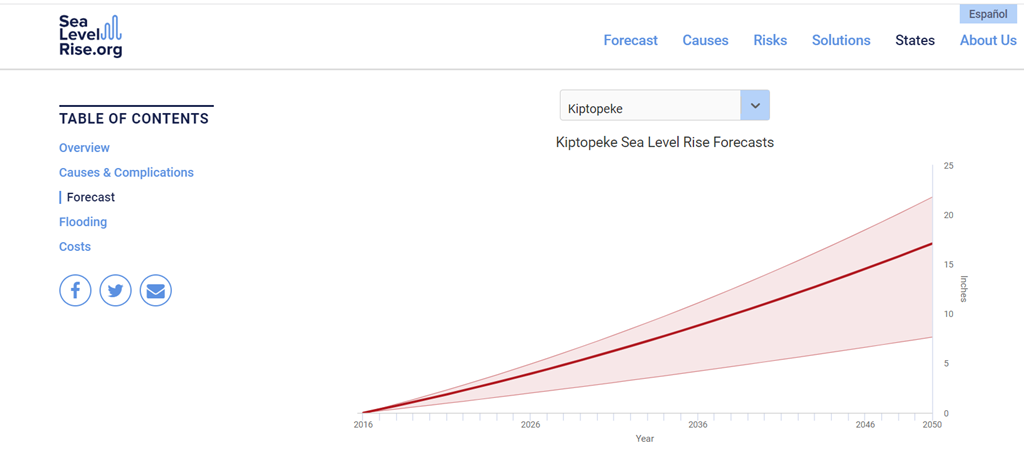

Because of warming waters and melting glaciers, the sea level rise at Virginia’s Eastern Shore has risen almost 3 inches since 2016, and the projected trajectory looks ominous. The region, sandwiched between the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, has one of the highest rates of relative sea-level rise on the Atlantic Coast. The Virginia Institute of Marine Science’s Center for Coastal Resource Management projects a relative sea-level rise between 4.5 to 7 feet by 2100, which is three to four times the global average.

Hampton, Virginia, which is right across the bay from the Eastern Shore area, is second only to New Orleans as the largest population center at risk from sea-level rise in the country.

UVA researchers are working on a new technology in hopes of helping at-risk communities like these adapt to the effects of rising waters.

Too Much and Too Little

Since the Virginia Eastern Shore land mass is no more than 50 feet above sea level at any given point, it easily succumbs to saltwater intrusion, accelerated sea-level rise and storm flooding intensified by climate change. Saturated soil and swells of groundwater destabilize buildings and can eventually cause the collapse of barns and homes. Farmland with elevated salinity cannot produce a healthy harvest — crops fail. Coastal erosion wears away soil and eliminates land altogether.

The predicament has been described as “too much” and “too little" — too much water where it’s not needed, for example intrusion and erosion, and too little where it is needed, such as not enough potable water.

Residents find it difficult to adapt to unpredictable environmental circumstances and their effects. Shore farmers, who have historically provided Virginia and the U.S. with a wealth of crops, now find that centuries of agricultural heritage are not enough to combat saltwater intrusion.

A group of UVA civil and environmental engineers and environmental scientists are teaming with local Shore residents on a project that aims to help these affected communities adapt to —literally and figuratively — an ever-changing landscape.

Empowering Communities with Technology

“We believe that the power of technology to transform communities and economies cannot be underestimated,” said Venkataraman Lakshmi, John L. Newcomb Professor of Engineering in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. Lakshmi is one of the lead researchers on the project team.

Their work is supported by the National Science Foundation with a $5 million grant aimed to support “Coastlines and People Hubs for Research and Broadening Participation.”

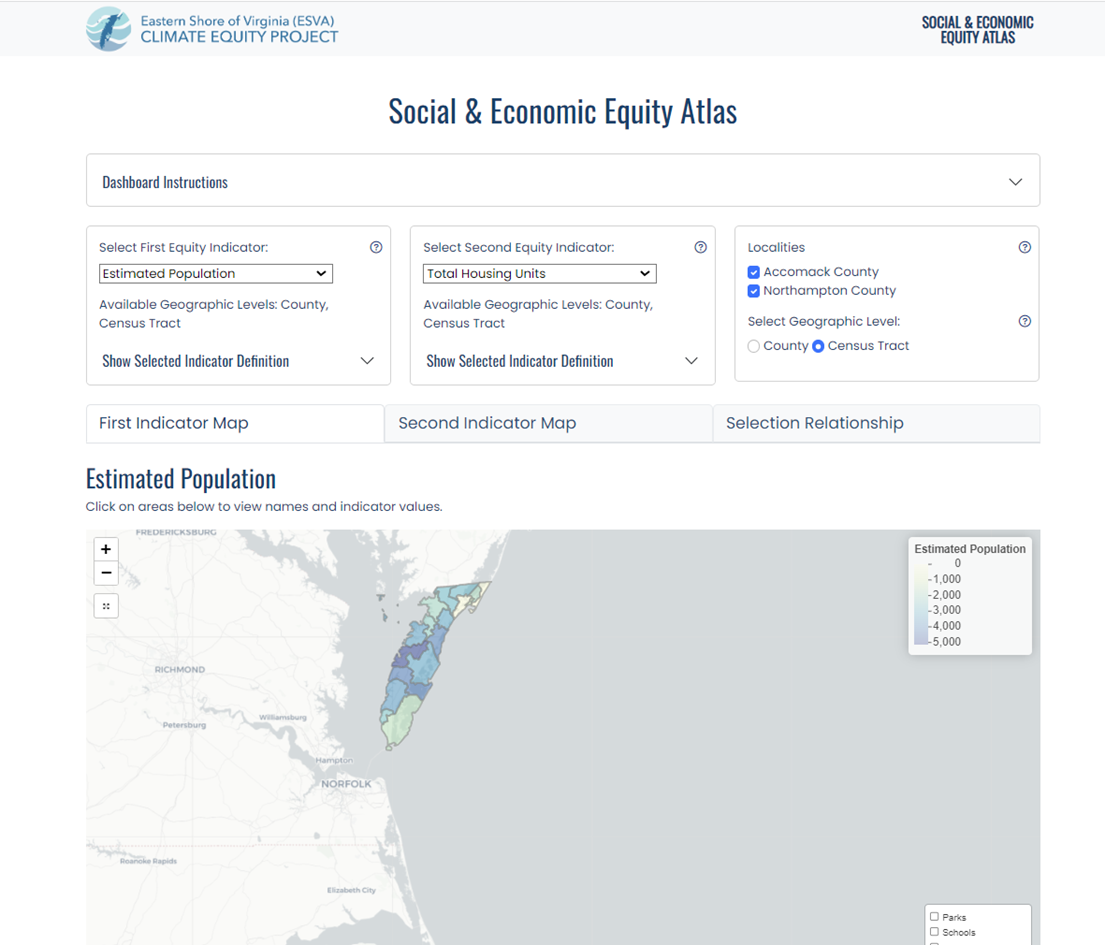

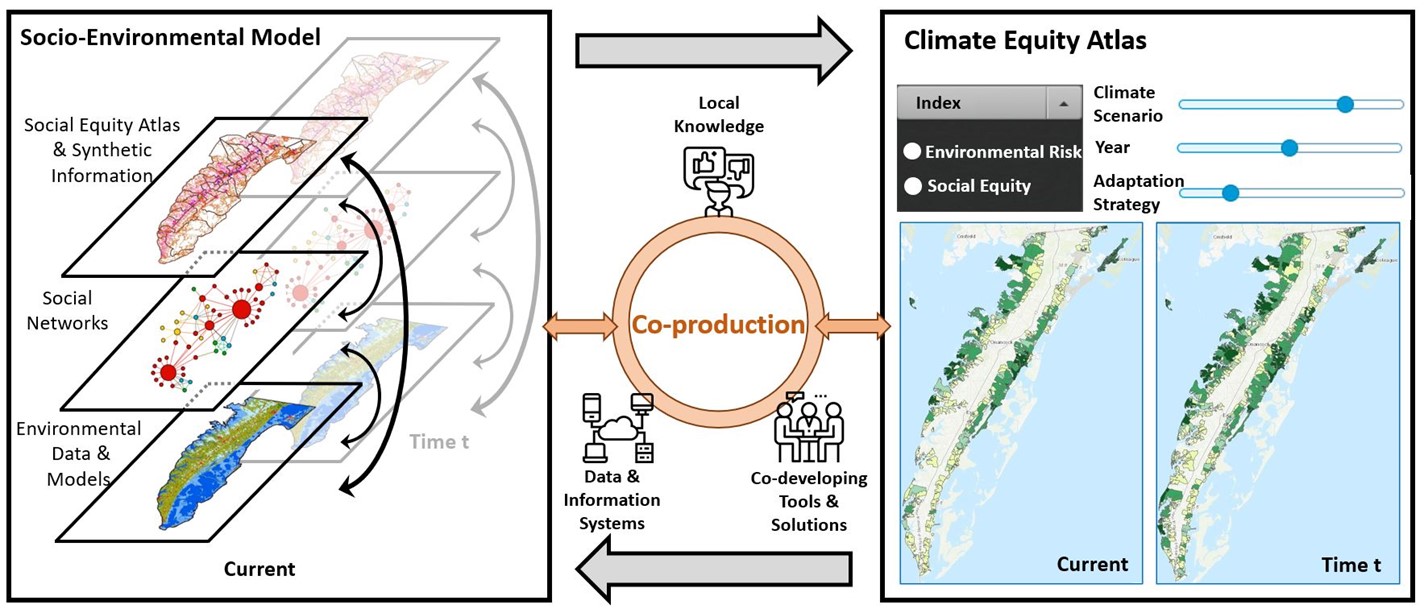

Researchers are developing a web-based decision-support tool that will help residents deal with the challenges caused by climate change. The tool, called the Climate Equity Atlas, combines historical environmental data and socioeconomic data to create a sophisticated predictive tool that empowers residents to make informed choices.

For instance, if your home collapses, where should you build a new one so the same incident will not occur again? Where is it most affordable to build? If your crops are ruined, is there a place on the Shore where the soil will support crops long term? Are there zoning limitations?

By engaging the community through events like the 2023 Eastern Shore of Virginia Climate Equity Project Winter Workshop, they are identifying issues like these and then designing the Atlas to incorporate the different scenarios and predict near-term and long-term effects of different choices.

“The Atlas will enable ‘what-if’ discussions and projections of alternative adaptation strategies,” said Majid Shafiee-Jood, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Adapting to Climate-Induced Migration and Displacement

With climate-induced migration being a stark reality, the tool is also an attempt to keep community members from leaving the area. By providing the information they can make decisions not only about housing and farming, but how to connect with shifting population hubs to sell crops, start businesses and implement economic development plans.

Other issues such as saltwater-tainted wells, unreplenished aquifers and dislodged septic systems are public health concerns. According to a report from the Virginia Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine spearheaded by UVA professor of civil and environmental engineering Jonathan Goodall, without intervention 209 miles or 13.8% of the shore’s road system could face permanent inundation as early as 2060.

The Atlas is a tool for governments and municipalities, too, so they can brainstorm adaptation strategies and remediation efforts for displaced people and infrastructure challenges — then use the tool to predict the effectiveness of different choices.

“We want to be able to tell who might be impacted — and who might be disproportionately impacted — by a decision,” Shafiee-Jood said.

Aiding Vulnerable Communities

Another main goal of the tool is to make sure no populations are left stranded without a path forward. The VASEM report also stated that lower income or racially segregated neighborhoods are often located in lower-value land tracts, including floodplains or flood-prone areas, and that residents and small businesses located in such areas are less likely to have the financial tools to protect their properties or relocate to less vulnerable areas.

“The research we’ve already done through VASEM on the impact of climate change can be plugged into the Atlas design,” Goodall said. “I’m thrilled that this data can help produce a tool so that this vibrant Shore community can continue to thrive.”

“We’re providing data in a way that can help the people in that region make decisions that put them in the best position to succeed,” said Duc Tran, a Ph.D. student gathering and analyzing the vast amount of critical environmental data needed to support this tool.

The Power of Data

“We’re being relentless about getting data,” Tran continued. “Because of our research, we found out that some National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and United States Geological Survey observatories have not collected data in certain years, so there were huge gaps in the environmental data. We’re utilizing remote sensing and lidar data to have more accurate predictions because we know the limitation of data availability is inevitable.”

Tran said he knows that with each component they build, they’re creating a foundation for resilience and for holding the community together. He hopes the things they learn and design for the Eastern Shore Atlas might be used to help other coastal communities around the world that are affected by climate change.