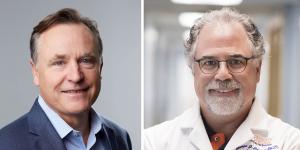

When it comes to the damage grenades and bombs do to soldiers’ bodies, George Christ, a University of Virginia professor of biomedical engineering and orthopaedic surgery, is on the front lines.

Christ, the director of the Center for Advanced Biomanufacturing and basic and translational research in orthopaedic surgery at UVA, has spent much of his career inventing ways to help wounded warriors recover from debilitating, large-scale muscle loss.

Even though Christ and other biomedical researchers have made great progress in developing technology for tissue repair, there isn’t a method for repairing major loss to muscles.

Until now. With the support of a $3.6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, Christ is developing a technology that could help soldiers on the battlefield, immediately after they are injured.

He has teamed with Kevin Edward Healy, the Jan Fandrianto and Selfia Halim Distinguished Professor in Engineering at the University of California at Berkeley, to develop a hydrogel material called Volumatrix that promises to change the face of traumatic injury care on and off the battlefield.

The team aims to refine its material until it’s similar to a freeze-dried sponge that can be carried around in a medic’s bag and placed directly in wounds. The sponge would soak up the blood, conform to the shape of a wound and do what is now impossible: regenerate missing muscle mass.

The team has already had a successful pilot project of its new sponge-like material. Healy designed the hydrogel to use the body’s natural cellular response to promote blood vessel formation and tissue integration. Christ is adapting it for wound healing, repair and regeneration in large-scale muscle replacement.

“The gel prevents the negative aspects of wound healing, like scarring, and it just lets the body go about its business,” Healy said. “And because it's a natural type of biopolymer, it seems that the body recognizes it. Then we use other tricks in biochemistry, bioengineering and material science to create a nice formulation for tissue regeneration.”

Bulking Up Is Hard

Hydrogels are commonly used for healing wounds. They form a specialized structure that cells recognize and “crawl into.” Once ensconced in their new home, the cells knit together to form new muscle cells, or whatever other types of cells have been called into service by the hydrogel design to enhance tissue repair. Hydrogel is made of a body-compatible material, so when the healing is done, the material is absorbed into the body and the gap in cellular structure — or wound — is replaced and repaired.

Christ and Healy are taking on the challenge of architecting a hydrogel that has enough structural integrity to stay intact while muscle cells inhabit the gel and knit together to fill the void.

“We have already created a gel that acts as a scaffolding for generating tissue. But that doesn’t help soldiers in the field because the gel needs to be prepared and mixed prior to application, which presents obvious challenges in complex environments brought by combat,” Christ said.

“The long-term vision is to make a portable, freeze-dried hydrogel sponge material that can be put into a medic’s kit,” he continued. “When placed at the site of injury, the sponge will soak up the blood to increase in size, similar to the way a household sponge works. The reconstituted sponge will then act as a strong, temporary, space-filling medical device that will provide structural support and allow the body to arrange new muscle cells for wound healing and tissue growth.”

“The Volumatrix device doesn’t use cells as the basis of repair like some regeneration technologies. It’s just a long chain of sugar molecules (polysaccharides) – a hydrogel of hyaluronic acid. This characteristic gives it a preservation capability and viability for the field,” Healy said.

Emergency Care That Lasts a Month

Replacing muscle any time is advantageous, but never more than on the battlefield. Repairs made with Volumatrix have the potential to help a soldier remain mobile, which increases the chances of survival for the soldier and the unit, since the military works in teams to stay safe.

Christ’s and Healy’s device could also keep a soldier active until he or she can get from the battlefield to a hospital and receive more comprehensive treatment.

In past conflicts, the term “golden hour” was used to describe the window of time in which field medics needed to treat soldiers and keep them alive until help could arrive. Because of the possibility of inaccessible ground terrain or lack of air superiority in future conflicts, the golden hour may change to the “golden week” or even the “golden month.” Soldiers could be trapped in austere environments like a cave, a desert or a jungle for a long time before a helicopter could transport them to a hospital.

Volumatrix could help medics and soldiers get through the wait, and it could eventually provide more benefits.

“After we develop Volumatrix to repair muscle, it’s possible that we can tune the material to include even greater capabilities. For example, we might add antibiotics for preventing infections or additives for stimulating cellular growth,” Christ said. “In this fashion we could facilitate and extend healing in a variety of ways – with the ambitious goal of complete functional recovery linked to faster return to duty or activity.”

“The device could also be used in civilian emergency care applications such as treating industrial workplace accidents and motor vehicle accidents,” Healy said.

Commercial Manufacturing to Make a Field-Ready Product

Not only is the Christ-Healy team trying to create an advanced hydrogel material that has incredible properties, they're also trying to create a material that is field-ready, which adds more challenges.

“If you want to put something in a medic’s pack, that means something has to come out,” Christ said. “So, whatever it is that you develop, it better be outstanding and absolutely necessary.”

The team is making sure the material is portable, lightweight and maintains its quality and sterility in the field. They have decided to freeze-dry Volumatrix to accommodate these requirements.

As part of the lab-to-field plan, the team will create a new company and work on commercial manufacturing.

“We're going to need to get this to industry to make it more consistent and reproducible,” Christ said. “There's the research and development and design part of it, but then there's the commercialization and production at scale so that we can get enough of it to test all our different scenarios back at the lab. This is also a necessary step for deployment to the field.”

The team hopes to name a CEO from the biotech field in the first or second quarter of 2023.

In the meantime, they are getting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s “Good Manufacturing Practices” manufacturing and sterilization processes initiated so that they can scale the raw materials and meet FDA requirements for use in humans.

“This is technically challenging even for experienced contract manufacturing companies, as scaling, GMP manufacturing and sterilization must all be achieved without affecting chemical and biological activity,” Christ said.

Making It Happen

To make Volumatrix a reality, Christ and Healy will have to be masters and commanders of three very different spheres in parallel: developing and testing the material at their respective university labs; managing FDA government regulatory requirements and documentation; and founding a company and commercializing a product in the biotech space. They are hoping to be ready for human testing in the next three years.

“We’re driven to make this happen. We think the technology is there. And the soldiers definitely deserve whatever we can do for them to improve their lives and mitigate their sacrifice,” Christ said