The engineers who gathered under the oculus of the Rotunda last week represented vastly different areas of expertise, yet they all had at least two things in common.

They’ve all been affiliated with the University of Virginia in the past, and they’re all examples of Black excellence.

Kicking off Black Alumni Weekend, the UVA School of Engineering and Applied Science welcomed the distinguished group of UVA-connected engineers back to Grounds on April 18 to talk about their lives, including past work and current projects.

Engineering Dean Jennifer L. West provided opening remarks for the speakers.

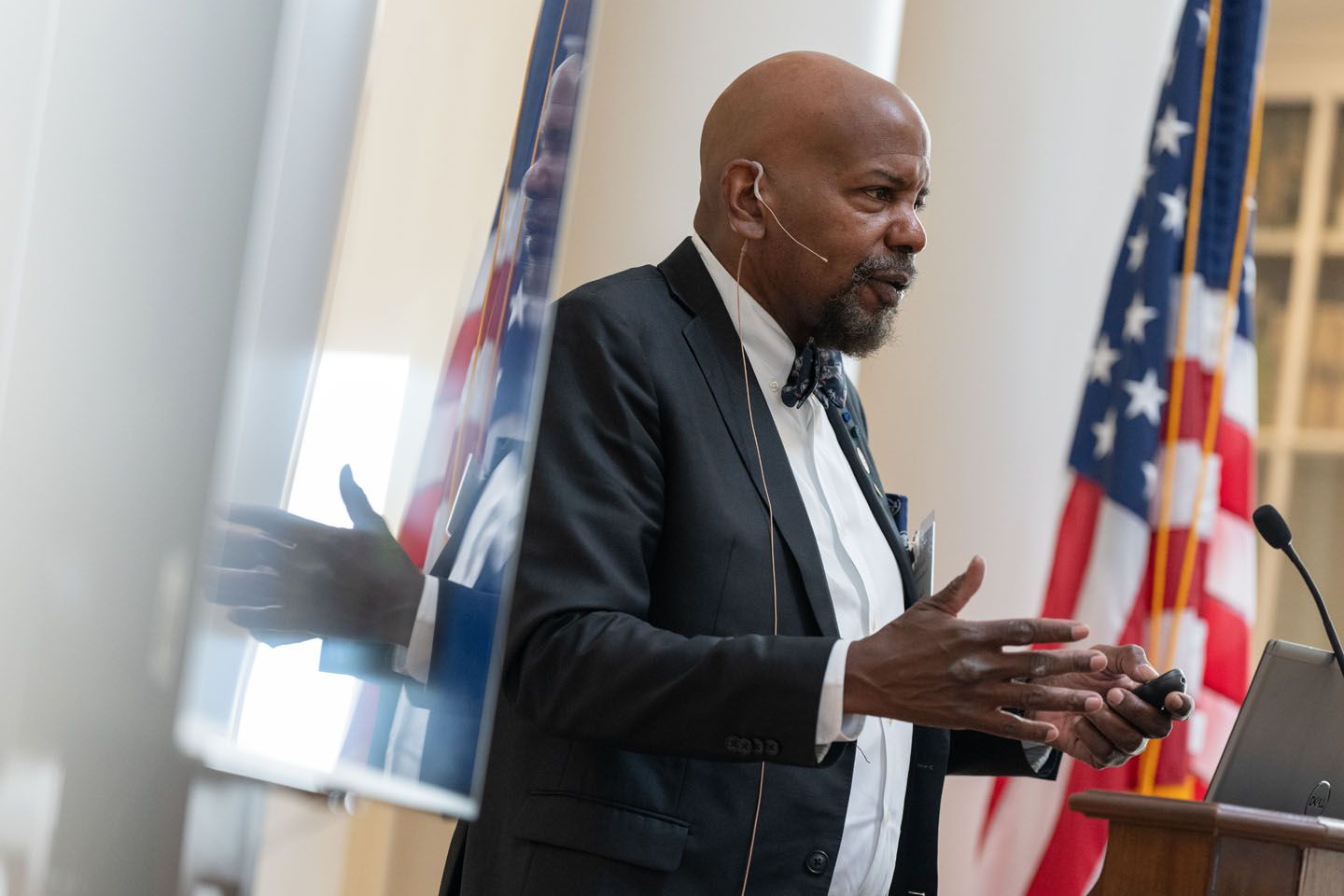

Cato T. Laurencin – Regenerating Body Parts

“If you do good things, good things happen,” said Dr. Cato T. Laurencin of the University of Connecticut.

The orthopedic surgeon is credited with pioneering the field of regenerative engineering. Laurencin is interested in finding new ways to recreate lost tissue and bone.

While he was on faculty at the UVA School of Medicine, the researcher invented the Laurencin-Cooper ligament for ACL regeneration.

National Geographic named the LC Ligament No. 30 on its 2012 list of “100 Scientific Discoveries that Changed the World,” and Scientific American named Laurencin to its “SciAm 50” list.

For his career accomplishments, President Barack Obama bestowed on him the National Medal of Technology and Innovation. He’s also won the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, among other top honors.

Laurencin takes his role as a mentor seriously. His efforts led to the increase of Black medical students by 50% while at the UVA School of Medicine. He said the difference between a sponsor and a mentor is that as a sponsor, “You kick the door open for them.”

In terms of regenerative engineering, he wants to keep going bigger, he said.

With a new class of stem cells and a host of talent working for him at the center that bears his name, he hopes to see entire limbs regenerated.

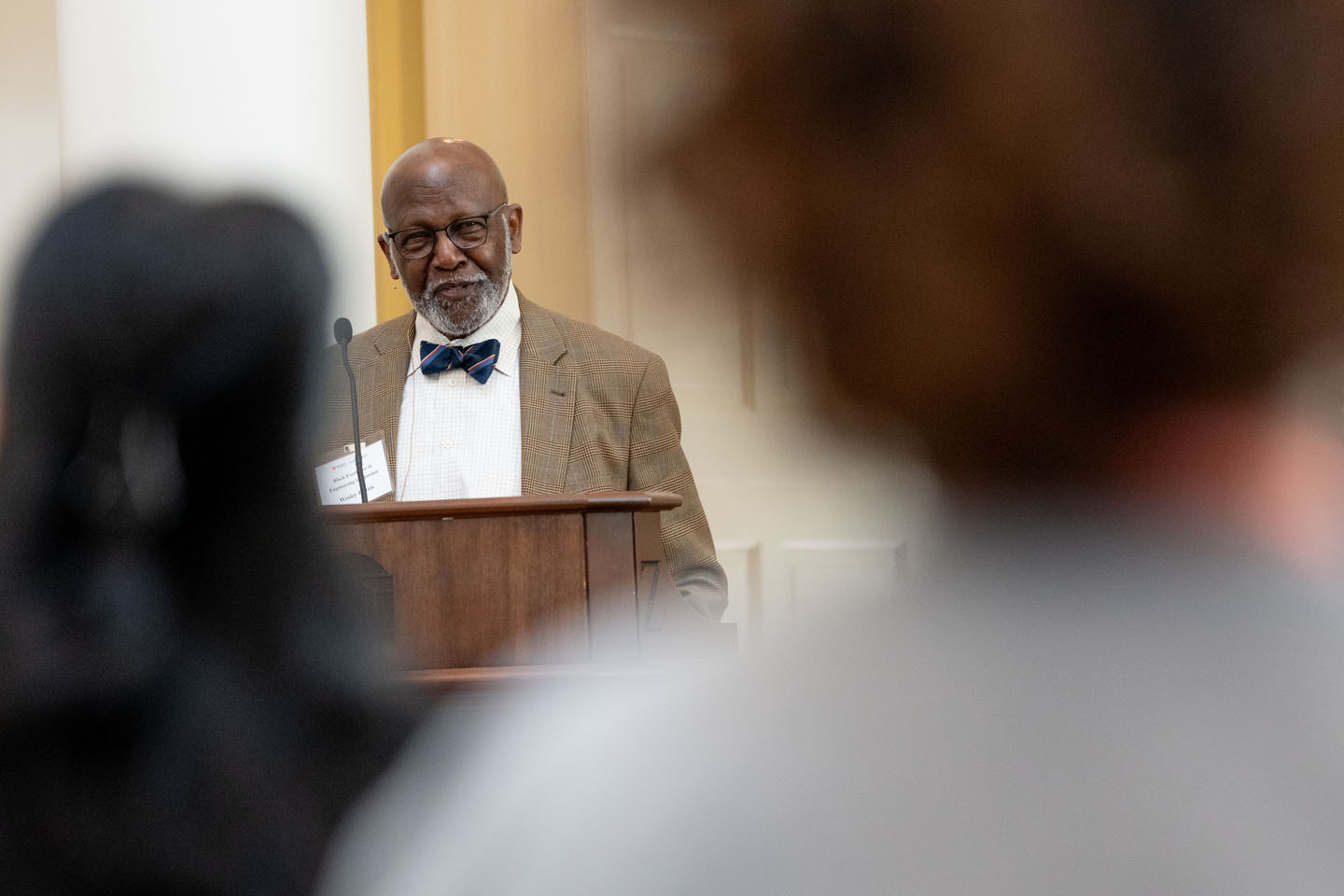

Wesley L. Harris – Blunting Shock Waves

Wesley L. Harris was UVA’s first Black professor to teach engineering, and the first African American to receive tenure here. The Class of 1964 graduate and former NASA associate administrator for aeronautics now works at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harris returned to Grounds to discuss how he has solved problems related to high-speed air movement during his career.

His research helped resolve the problem of noisy military helicopters, which could be more easily identified and shot down. He also studied the upward propagation of sonic booms on supersonic airplanes. Vertical movement blunts the noise problems created by aircraft that break the sound barrier.

“That research was actually started at UVA in the wind tunnel designed here,” Harris said.

More recently, he has investigated sickle cell disease, with an eye toward reducing shock for sufferers. The red blood cell disorder affects African Americans disproportionately.

While a student at UVA, Harris was recognized by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics for his research into the flow of air over wing surfaces. He was also the first African American member of the Jefferson Society.

He had the honor of introducing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., when King spoke on Grounds in 1963.

Harris said his life has been a tribute to his inspirational high school teacher, Eloise Bose Washington, who encouraged him to go to UVA after a third-place finish at the state science fair held here. They thought he should have placed higher, given the quality of his work and his winning the Black science fair.

Though lingering segregation meant he couldn’t enter UVA’s physics program, his first choice, because it was still prohibited, Harris took UVA engineering courses with no regrets. He wanted to show the state’s flagship university how Black students could excel.

Harris went on to become the first UVA aeronautical engineering student to graduate with honors. He then earned his master’s and doctoral degrees from Princeton University.

Paul Mensah – Scaling Up the COVID-19 Vaccine

Paul Mensah, the vice president who oversees clinical supplies for Pfizer’s biotherapeutic and vaccine portfolio, was part of the team that scaled up and rolled out the now-famous Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.

The chemical engineer earned his master’s and Ph.D. at UVA in 1997 and 1999 respectively.

Learning of the vaccine’s 95% efficacy, and then being able to provide it on a mass scale at such an uncertain time was “one of the highlights of my career,” he said via Zoom.

Mensah explained the complexities of the work. Proof of concept in the lab is one thing. Providing large quantities of the vaccine in short order, then delivering them across the globe was another.

“MRNA are inherently unstable,” he explained.

In fact, to ensure efficacy following shipping and storage, the vaccines needed dry ice. “There wasn’t enough dry ice in the world,” he said, “so we made our own.”

For this and other contributions, he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2022.

Mensah also detailed his journey as an immigrant from Ghana to the Bronx, and then on to college in Ithaca, New York, before arriving for graduate school at UVA.

“I finally felt like I fit in,” he said of his time in Charlottesville.

Archie L. Holmes – Engineering Education Delivery

At the University of Texas, Archie L. Holmes, Ph.D., supervises an academic budget worth billions of dollars as executive vice chancellor of academic affairs.

But his beginnings were as a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UVA. He took an early interest in infrared light, he said. Infrared is key to any number of modern applications, such as semiconductor devices that need minute infrared beams to operate.

Holmes said during his Zoom presentation that engineers often make a logical fit as administrators.

In the case of his current job, he asked himself, “How do I take a very complex system, and make it so it delivers on things society needs?”

Before leaving UVA, Holmes rose from faculty member to associate provost.

UVA President Jim Ryan praised Holmes before his departure for managing the movement of all spring courses online “within a matter of days” during that first spring after the pandemic hit.

UVA Faculty – Expanding the Boundaries of Science

In addition, UVA Engineering professors Devin K. Harris, Rosalyn W. Berne, Thomas Ward, David Green, Lakeshia Tate and Daniel Abebayehu provided updates on their work.

Green, for example, is collaborating with the UVA School of Medicine on developing more effective personalized drug delivery therapies at the nanoscale. With current cancer therapies, only about 1% of the particles get to the target, he said.

Before talking about himself, Green noted that several of his family members have UVA or other academic affiliations. He also acknowledged his Charlottesville ancestors.

“My father’s mother’s family is from here,” he said. “Some were freed, but some were slaves working local plantations for UVA.”

Green said those family names are now etched on the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which is not far downhill from the Rotunda.