Chemical Hazards

This section introduces the hazards of chemicals and routes of exposure to them in the laboratory. Additional information can be found on the EHS website in the Chemical Hygiene Plan.

Hazard Classifications

Hazards are the inherent harmful characteristics or properties of a substance, operation, or activity, regardless of the quantity involved or method of use. Chemicals can pose a variety of hazards to human health and physical injury, including:

Health Hazards

- Toxic

- Carcinogenic

- Mutagenic

- Reproductive toxins

- Sensitizers

- Irritants and Corrosives

- Asphyxiants

Physical Hazards

- Combustible

- Flammable

- Explosive

- Reactive or pyrophoric

- Oxidizers

- Corrosive

- Compressed Gas and Liquids

- Cryogenic liquids

Some chemicals pose both health and physical hazards. For example, inhalation of benzene vapors can result in central nervous system narcosis, direct skin contact can defatten skin, and long-term exposure has been demonstrated to increase the rate of leukemia. As a flammable liquid, benzene can also result in serious burns or cause a structural fire if it is accidentally ignited.

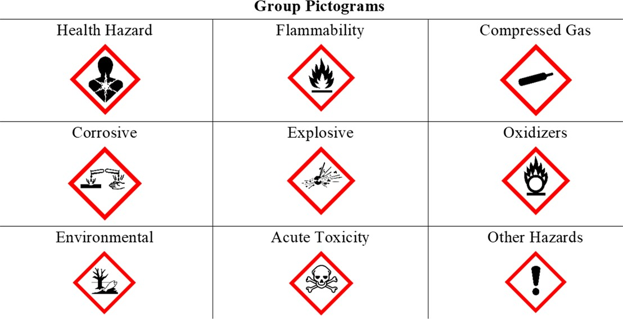

Hazard classifications of substances, chemicals and mixtures can be found in Safety Data Sheets (SDS). They follow a globally harmonized system (GHS) to ensure consistency in the presentation of important safety information about a chemical. The GHS classifies chemicals into nine major hazard groups shown in this table,

While the hazards of a particular chemical reflect inherent properties of the chemical, the actual risk of injury or illness is a function of both hazard and exposure. Regardless of the route, the exposure may consist of a brief or even one-time (acute) exposure, or it may repeatedly occur over longer (chronic) periods of time. Efforts that minimize exposure will limit risk of harm.

Routes of Exposure

Chemicals exert harmful effects on the body through exposure by one or more of the following routes: Ingestion, Inhalation, Dermal (skin) contact, and Percutaneous (puncture).

- Ingestion refers to eating or drinking a substance and can also include, to a lesser extent, swallowing mucous containing a substance that was inhaled into the upper respiratory system. Ingestion is the most common route of poisoning in homes with small children but is rare in laboratory settings due to restrictions on smoking, eating, or drinking. Individuals handling hazardous materials must nevertheless still take precautions against inadvertent ingestion by carefully controlling contamination, especially on the hands.

- Inhalation and dermal (skin) contact are the more common routes of chemical exposure in most laboratories. Inhalation can generally be controlled effectively using a local exhaust ventilation device such as a chemical fume hood or exhaust snorkel when handling volatile substances or performing operations likely to splash or aerosolize. Dermal contact can be limited through careful work practices that minimize contamination such as the use of tongs or forceps, good housekeeping, and the proper selection and consistent use of gloves.

- Puncture exposures occur when intact skin is punctured by a sharp or pointed object and contamination on the object is introduced into the body. These so-called “Sharps” injuries not only physically damage tissue but are also responsible for a large proportion of laboratory- and clinically acquired infections. Within chemical laboratories, puncture wounds and percutaneous exposures can be minimized by:

- Replacing sharp needle syringes with blunt cannula devices,

- Eliminating Pasteur pipettes,

- Substituting safety blades and scalpels for straight-edge razors,

- Using forceps for collecting broken glass or dropped needles and syringes,

- Adopting one-handed techniques and not recapping needles.

Signs and Symptoms of Over-Exposure

Information about the hazardous properties of chemicals, including typical medical signs and symptoms of over-exposure, is available from container labels, Safety Data Sheets, and other references and resources.

The signs and symptoms of over-exposure vary widely by the chemical, concentration, route of exposure, and individual health and medical conditions. In addition, over-exposure to many chemicals may not result in immediately recognizable signs or symptoms.

However, should any of the following symptoms develop, individuals should stop work immediately, remove PPE, wash their hands, and contact their Healthcare provider:

- Unusual taste or odor,

- Respiratory irritation, coughing, choking, or shortness of breath,

- Sudden headache, dizziness, blurred vision, or loss of consciousness,

- Burning or painful sensation,

- Swelling, reddening, or itching skin.

Particularly Hazardous Substances (PHS)

OSHA’s Laboratory Standard identifies Particularly Hazardous Substances as several categories of chemicals that pose serious and potentially irreversible health hazards. They include select carcinogens, reproductive toxins, and acutely toxic chemicals. Due to their significant potential for harm, work with these substances requires adoption of additional safe working practices to further control exposure. Please contact EHS for help in identifying Particularly Hazardous Substances or for assistance in evaluating the hazards from these or any other chemicals.

- Select Carcinogens are the subset of chemicals known or reasonably anticipated to cause cancer in humans based upon epidemiological research or animal testing. They include chemicals identified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the National Toxicology Program, and those specifically regulated as carcinogens by OSHA.

- Reproductive Toxins are those chemicals that can negatively affect human reproduction or reproductive capabilities. They include chemicals that can damage reproductive organs or their function, cause mutations to inheritable genetic material (mutations in sperm or egg), or cause malformations to a developing embryo or fetus (teratogenesis).

- Acutely or Highly Toxic chemicals are chemicals that cause serious illness or death after exposure to small quantities or at low concentrations.

Other Regulated or High Hazard Chemicals

In addition to the Particularly Hazardous Substances specifically addressed by OSHA’s Laboratory Standard, many other chemicals pose serious hazards or carry special regulatory requirements.

- Toxins are widely used in biological research. Due to their high toxicity, many are regulated by the Federal Select Agent Program. Select agent toxins include toxic materials and toxic products from biological organisms and recombinant or synthesized molecules and can pose a severe threat to public health, animal or plant health, or animal or plant products. Laboratories interested in working with these or any other highly active toxins must first consult EHS and UVA’s Institutional Biosafety Committee.

- Hydrogen Fluoride and Hydrofluoric Acid can cause severe, penetrating burns to the skin, eyes, and lungs. Although concentrated forms of these compounds are readily perceived by a burning sensation, more dilute forms may be imperceptible for hours, potentially leading to insidious and difficult-to-treat deep burns. Seek medical treatment for any exposure to HF and

use Calgonate® gel for topical first aid treatment as soon as you have an exposure. Be mindful that the product has a roughly 1-yr shelf life. Laboratories interested in or already working with HF should consult with EHS (and for supplies of Calgonate® gel).

- Heavy Metals are toxic in most forms and some, in their organic form, are extremely toxic and highly permeable to most gloves and other personal protective equipment. Laboratories interested in or already working with heavy metals (arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, hexavalent chromium, lead and mercury) should contact EHS for a hazard assessment. In many cases, and especially when handling powders, EHS will recommend the laboratory have an Industrial Hygienist (EHS) conduct periodic sampling to determine potential for exposure. Based on sampling results, EHS can provide additional recommendations.

Highly Reactive and Explosive Compounds

Highly reactive compounds include chemicals that are unstable and capable of self-decomposition or that react violently when exposed to water, humid air, oxygen, light, heat or friction, physical shock, or other chemicals. These reactions are highly exothermic and may also evolve toxic or flammable gases. They include water / air reactive and pyrophoric chemicals, azo compounds, peroxides, and peroxide-forming chemicals. Some highly reactive compounds are shipped and stored under mineral oil, solvent, or an inert atmosphere to minimize the potential for contact with air or water.

- Alkali metals (e.g., sodium, potassium), some metal hydrides (e.g., lithium aluminum hydride, calcium hydride), and pyrophoric chemicals (e.g., organo-lithium compounds) react violently when exposed to water, humid air, or oxygen.

- Pyrophoric materials often react so rapidly that actual ignition occurs. Depending upon the location of work and the other chemicals in use, unexpected ignition can result in serious fires and life-threatening burns. Note that EHS provides an on-line training module specifically on Handling Organolithiums and Related Agents, available through the STAR training portal.

- Explosives are a broad category of chemicals with the potential to release such large amounts of gas that they generate a high-pressure shock wave capable of causing serious physical damages. Explosives can be initiated by mechanical impact, heat, light, or chemical reaction. In the laboratory, explosives may be under purposeful study but are more commonly encountered as accidental by-products, residues, or decomposition products.

- Azo compounds and peroxides are highly sensitive to physical shock, heat or friction, and sparks. Many require storage below room temperature. Some common laboratory chemicals can also form potentially explosive peroxides over time, even when stored in sealed containers. Manufacturers sometimes add inhibitors to these compounds to retard peroxide formation.

- Chloroform can form very toxic phosgene over time when exposed to oxygen and amounts of UV light (or if contaminants are present). Unstabilized chloroform should be discarded 6 months after opening and stabilized chloroform discarded after 12 months.

- Peroxide-forming chemicals should be purchased in amber bottles and stored under dark conditions. In general, the preferred method for safe management of these chemicals is to purchase them in the smallest quantity needed, date label their containers, and discard them as hazardous waste before the manufacturer’s expiration date.

- Class A compounds should be disposed of within 3 months of receipt.

- Class B compounds should be disposed of within 6 months of receipt.

- Class C compounds (and Class B with stabilizers) can generally be stored for longer periods of time but should be visually inspected at least every 6 months.

- The table below describes the three generally recognized classes of peroxide-forming chemicals and provides some common laboratory examples of each. Additional information on peroxide-forming chemicals is available from Safety Data Sheets, technical references and EHS.

Class A

Chemicals that form explosive levels of peroxides without concentration:

- Butadiene

- Chloroprene

- Isopropyl ether

- Potassium amide

- Sodium amide

Class B

Chemicals that form explosive levels of peroxides upon distillation or evaporation:

- Cumene

- Cyclohexene

- Diethyl ether

- Dioxane Furan

- Tetrahydrofuran

Class C

Unsaturated monomers that can auto-polymerize if inhibitors have been removed or depleted:

- Acrylic acid

- Butadiene

- Ethyl acrylate

- Methyl methacrylate

- Styrene

- Vinyl acetate

- Perchloric acid, picric acid, and sodium azide are three additional chemicals that can pose serious explosion hazards. These three chemicals pose little risk of explosive reaction when kept wet by solution in water. When dried, however, their residues (as perchlorates, picrates, and azides) can become shock, friction, and heat sensitive, and frequently accumulate under bottle caps over time.

- Controlled Substances are drugs, drug-like substances, and certain precursor materials that are regulated by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and by the Virginia Board of Pharmacy (VBP). Researchers planning work with controlled substances must first obtain Practitioner registrations from both the DEA and VBP, and meet specific laboratory security, inventory control, and user authorization requirements. Current lists of controlled substances and registration requirements are available from the DEA and VBP websites.

- Chemicals of Interest - Department of Homeland Security -Several hundred chemicals are regulated under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Chemical Facility Anti- Terrorism Standards (CFATS). DHS has established screening threshold quantity limits for each of the chemicals of interest under different accident or terrorist scenarios. Chemicals of interest must be kept secure from unauthorized access. Copies of the current list of DHS chemicals of interest can be obtained from the CFATS website or by contacting EHS.