Final exams are nigh, the holiday break almost here. ’Tis the season to ask: Is it better to A) give or to B) receive?

The answer is both can be equally valuable.

For proof, look no further than the University of Virginia School of Engineering Applied Science chemical engineering professors who trebled their teaching toolkits earlier in the academic year. That’s right, it was chem-e to the power of three in an exercise known as a “Teaching Triangles,” an approach borrowed from Duke University.

What Exactly Is a ‘Teaching Triangle’?

Matthew J. Lazzara, a professor of chemical engineering and biomedical engineering who convened the Teaching Triangles group and coordinated the participating faculty, said the idea was relatively simple. Instructors teamed up into groups of three, sat in on each other’s courses, then reflected:

- Was there a practice they might want to bring into their own classroom?

- Would one of their own practices work in a colleague’s course?

- How might changes influence student engagement?

Lazzara said the reason a three-person group works for the exercise is because a simple pairing might be too limited, while four or more might be unwieldy for the purposes of coordinating schedules.

“You get more than one observation of any instructor, but it’s still a small group,” Lazzara said. “Everyone really has to participate and get to know each other.”

He added that the triangles were equilateral. Nobody, no matter how experienced, positioned themselves as the “master.”

“Everyone was genuinely there to learn from one another regardless of rank,” he said. "I actually think that faculty who have more recently completed their training have a better understanding of how to connect with students today.”

Lazzara said he put his own spin on the concept. Teams were broken into Red, Gold, Green and Blue “squadrons,” inspired by the “Star Wars” films.

For Improved Results, Try These Angles

The following is a sampling of some of the teaching insights the professors gleaned. While what works for some classrooms might not work in others, these approaches resonated:

15-Minute Lectures

One way of teaching is to lecture for the length of the allotted course time. Another is to break topics up into more digestible chunks.

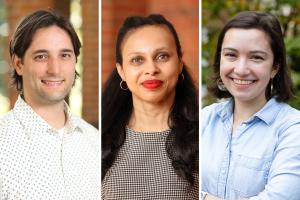

Camille Bilodeau said the latter worked very well for Lakeshia Taite’s asynchronous summer course on material and energy balances. Each 15-minute exploration built on the previous one.

“She guided students through practice problems in a very clear, organized manner,” Bilodeau said. “Even though my classes are not asynchronous, I may add review lectures to a few classes as supplemental materials for my students.”

‘Think-Pair-Share’

“I like to incorporate occasional ‘active-learning breaks’ into my lectures,” Jason Bates said. “These short, 5-to-10-minute interludes help keep students engaged by having them work together on a problem or discuss concepts in pairs, then share with the class (“think-pair-share”).

“While they work, I circulate and answer questions.”

Self-Assigned Homework

“Some of my colleagues have great creative ideas for projects that help students think differently about the material besides the traditional homework/exam structure,” Bates said. “One I particularly like that I may use in the future is to have the students create their own homework problem on any topic in the course.”

The reason, he said, is that the students themselves know best where they are weakest and can use improvement.

Student-Produced Video

Lazzara said he was impressed by how many actionable ideas he observed when visiting Kyle Lampe’s and Nick Vecchiarello’s courses.

“Kyle, for example, asked students to create educational videos on a particular topic,” Lazzara said. “It seemed like the students really enjoyed that, and I was really fascinated to see how good they were. That spurred me to see if could use the same approach in my grad class with students working as a group to prepare something. Students could make a presentation, even if it were just a homework assignment, to learn to communicate better.”

Commonality Reinforced What Works

Lazzara said the overall exchange of ideas is what made the exercise a success, including reinforcing shared approaches and understandings.

“I learned a lot by hearing all of the groups talk about what was common across the four groups,” he said.

Ian Mullins, a sociologist with the UVA Center for Teaching Excellence, sat in on the Teaching Triangle discussions to facilitate and offer his own thoughts. University of Virginia professors who are interested in requesting the center’s resources can make a teaching consultation request online.