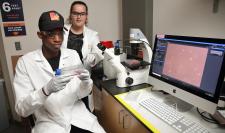

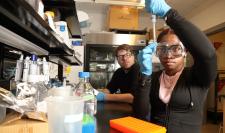

Caleb Tyson squinted at clear liquid in a lab vial, where he should have seen solids floating within. Something had gone wrong with the peptide – a string of amino acids – he and his two lab mates were trying to make.

They would have to figure out their mistake and make the peptide again before they could move on to the next step toward their ultimate goal, creating a degradable polyurethane material with promising properties for treating bone tissue injury.

Learning to expect setbacks is part of the point of research programs for undergraduates like the one Tyson participated in at the University of Virginia this summer.

Internship Offers a Two-Way Partnership

Tyson is a rising third-year chemical engineering major at Hampton University, a historically Black university in Hampton, Virginia. He is working in assistant professor of chemical engineering Lakeshia Taite’s biomaterials lab at the UVA School of Engineering and Applied Science through a new program that both schools hope results in a long and fruitful relationship.

The idea is to offer Hampton’s chemical engineering majors summer research internships with UVA faculty advisors and graduate student mentors — and for the students to continue the projects after they return to Hampton, establishing ongoing collaborations.

Along with Tyson, rising third-year Lauran Pearson is working with associate professor Kyle Lampe and assistant professor Rachel Letteri, and rising fourth-years DessaRae Lampkins and Alex Harmon are working in the Lampe lab and assistant professor Steven Caliari’s lab respectively. Taite, Lampe, Letteri and Caliari all specialize in biomaterials and tissue engineering.

The internship is modeled after the National Science Foundation’s prestigious Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, with an eye toward seeking NSF funding. The faculty are developing an NSF proposal incorporating this summer’s outcomes.

Building relationships with undergraduate programs at other universities has long been on Department of Chemical Engineering chair William Epling’s to-do list, and Hampton University was of particular interest.