Fourth-year student Liam Colbert scrolled through the project’s Gantt chart on his laptop, displaying a daunting spreadsheet of color-coded tasks and timelines.

Colbert’s chart is a visual representation of months of hard work by a team of University of Virginia engineering students tasked with creating a high-tech training tool for one of the best university swim teams in the country.

Their challenge? Develop a “smart starting block” that could measure a swimmer’s force at takeoff and potentially help UVA’s elite athletes shave precious fractions of a second off their times.

Smarter Starts for Faster Swims

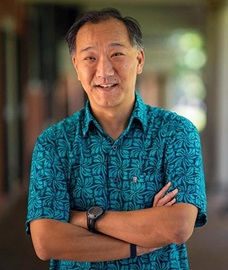

The idea came from Ken Ono, a UVA mathematics professor and a professor of electrical and computer engineering by courtesy, who collaborates with the UVA Swimming and Diving Team and head coach Todd DeSorbo to minimize inefficiencies in swimmers’ strokes using video and data analysis.

The UVA swimming team has established itself as one of the nation’s elite programs, consistently winning NCAA championships and producing world-class athletes, including Olympians.

Ono wanted to know if modifying a swimmer’s stance on the starting block could improve their explosiveness at the start of the race when they dive into the water.

“The starting block is a piece of equipment that actually has nothing to do with swimming,” Ono noted. “It has to do with the launch of an athlete into a pool.”

For competitions, the swimmer’s platform, called a block, has an adjustable wedge at the back, providing swimmers with additional leverage as they push off. The wedge can be moved forward or backward to accommodate different foot placements. Swimmers typically place their back foot on the wedge to generate maximum force during their launch at the start of the race. Ono believes that many and perhaps most swimmers can improve the explosiveness of their starts by determining the optimal foot placement — and improve their overall time.

What was needed was a highly sensitive, highly specialized piece of equipment that could test his theory. So Ono wanted to see if some of the engineering students could create a force sensor system for the block that could be used in training to capture data for this purpose.

The project was a perfect fit for the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering’s capstone course, where fourth-year students apply what they’ve learned to real engineering problems. But the students would have to work fast. Ono and DeSorbo hoped to have the equipment available for testing before the winter break, as the swimmers prepared for spring competitions.

“Our students built a tool that could help top athletes perform even better — just one example of how engineering can turn ideas into real-world impact,” said Scott Acton, professor and chair of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

I’ve been a swimmer my entire life. I thought it would be really cool to work on a project where I got to continue that passion and make an impact at UVA.

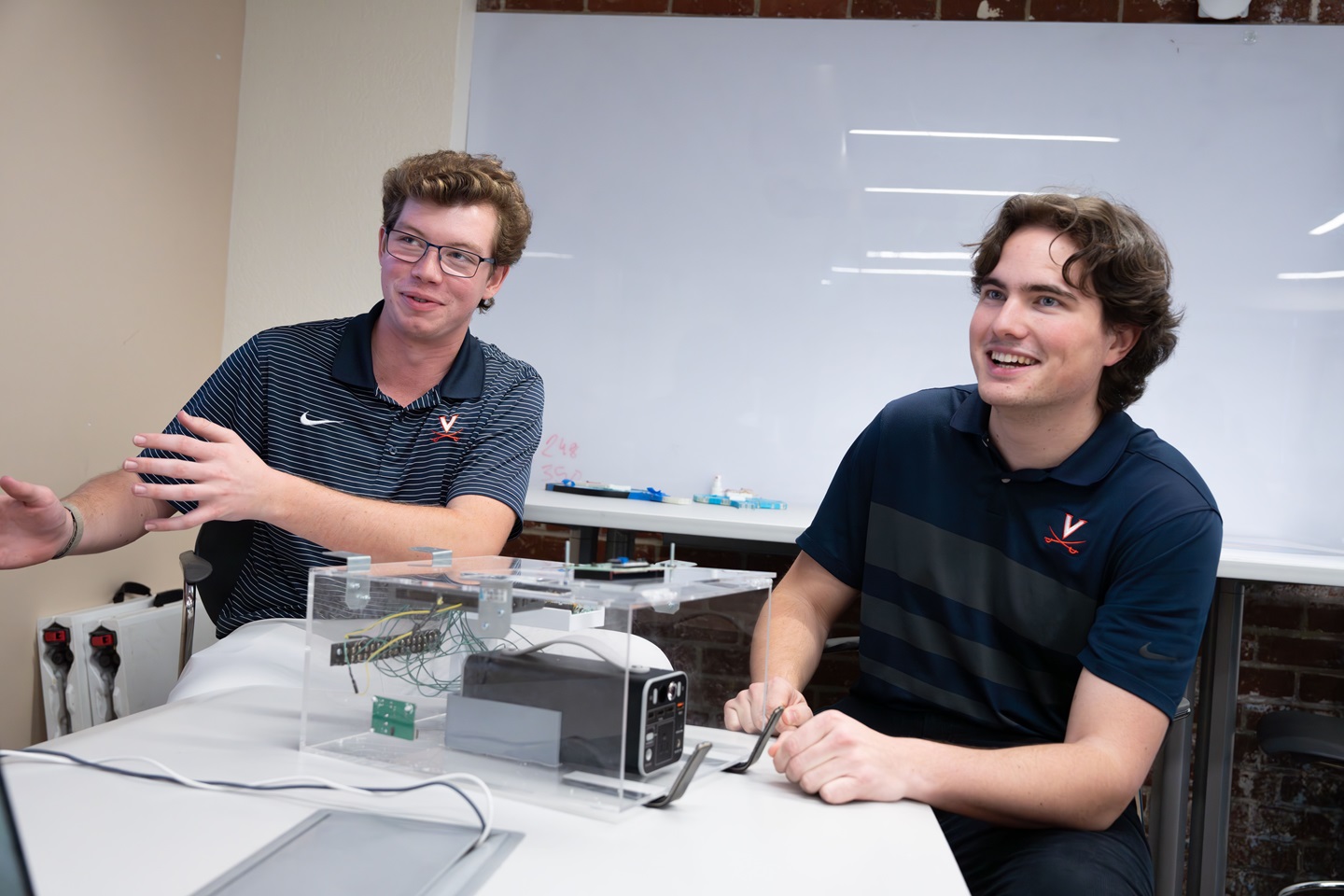

The capstone team was made up of five students, each tasked with a different area of responsibility: mechanical, electrical, microcontrollers, systems integration and software. Three of the team’s students — Colbert, Preston Borden and Meghana Guttikonda — all swam competitively before college or at the club level.

“I’ve been a swimmer my entire life,” Guttikonda said. “I thought it would be really cool to work on a project where I got to continue that passion and make an impact at UVA.”

Sink or Swim: Capstone Students Apply Their Training

The involvement of Adam Barnes, the senior lecturer who oversees the electrical and computer engineering capstone students, was also fortuitous. He is an expert in designing, building and calibrating custom sensor products.

Andy Chen, the mechanical lead, noted, “There’s already a super expensive commercial version out there, but we were building ours from scratch, just for the team. That’s what made it so exciting — we had to figure out how to make it work without a blueprint.”

The smart starting block needed to do three key things: integrate seamlessly with the existing NCAA-standard block, measure the force a swimmer exerts at takeoff (what Ono calls “explosiveness”), and deliver real-time data to the coaches and athletes.

“The mechanical portion of our system involved designing the physical surfaces that swimmers would interact with to get force data to our sensors,” Chen explained. “Because the sensors would not be used in competition, the priority was to seamlessly integrate these sensing surfaces into the start block so that swimmers feel little to no difference from the standard NCAA block.”

To achieve this, the students designed a sensor-embedded sleeve for the block’s flat, front-facing surface. They also attached sensors to the adjustable back wedge, sandwiching them between layers of clear acrylic to protect the electronics.

On the electrical side, Colbert worked closely with Sammy Knorr, the microcontroller lead, to make sure the electronic “guts” of the box worked as envisioned. This unit transmitted data wirelessly to a display screen on the swim team’s custom software app on a phone or computer for deeper analysis. The app even tracks swimmer history and peak performance data. Borden was the systems integration lead, focusing on developing ways for the hardware to communicate with the software and ensuring seamless data transfer between components.

“The software has three main parts,” said Guttikonda, the software lead. “First, there’s the swimmer registration page. Then, there’s the magnitude recorder page, which pulls data from the microcontroller and displays it for the swim coach. Finally, the swimmer progress page tracks and visualizes performance over time.”

“We had weekly or sometimes biweekly meetings with the capstone group,” DeSorbo said. “And every week, I was seriously impressed with what they were doing. They’re professionals.”

Shaving Time Off the Block

UVA swimmer Emma Weber was among a small group of swimmers who participated in the tests during training, looking to see if she could improve the already-successful stance she used last year to bring home the Olympic gold for the women’s 4 x 100-meter medley relay.

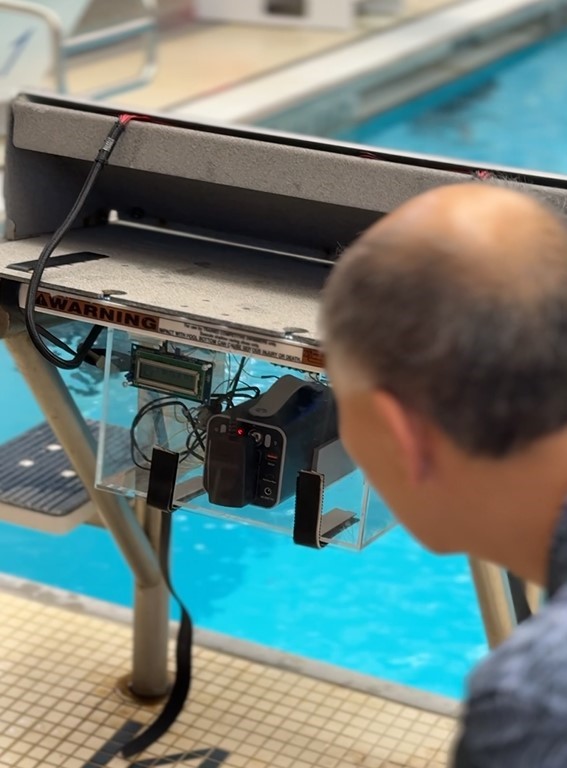

Now it was time to test the device at the pool.

“By modifying her position and moving the wedge back about 3 inches — the starting block, that is — her explosiveness went up 30 percent,” Ono reported. “We’ll take that any day.”

Knorr added, “She always had it [the wedge] in position two for as long as she could remember. But by taking her height into consideration and moving it back to position four, she was able to achieve 30 pounds more force by moving it into that position.”

“The capstone team had a small budget and one semester to come up with a solution,” Barnes said. “And while it doesn’t have all the bells and whistles of a commercial device, it still provides extremely valuable information to the swim team, with an especially usable interface on the app.”

The coach added that he is looking forward to seeing how the new system advances, as next year’s capstone students will likely develop the equipment further.

“Having academics helping out athletics was probably one of the most impressive things,” DeSorbo said.

“I think we are the only school that has a world class swimming team and a world class engineering program that actually work together,” Ono said.

Ono said he’s looking forward to making the technology more widely available to UVA’s swimmers.